Despite having been around for just 50 years, microprocessors have become the backbone of modern society, and their influence is only expected to increase from here on out. Given its tremendous importance, it’s a good opportunity to reflect upon the 4004, the tiny chip that started it all.

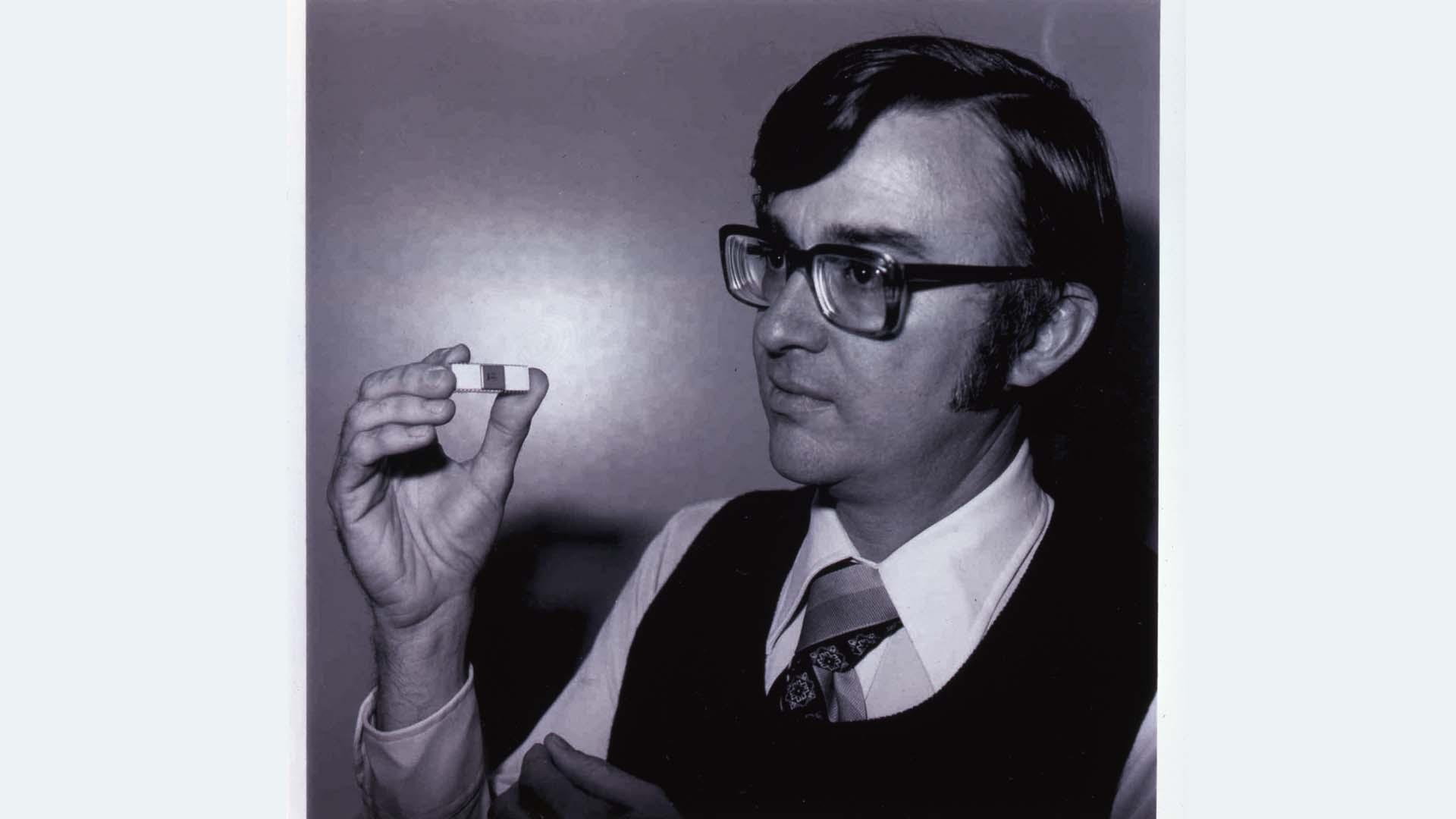

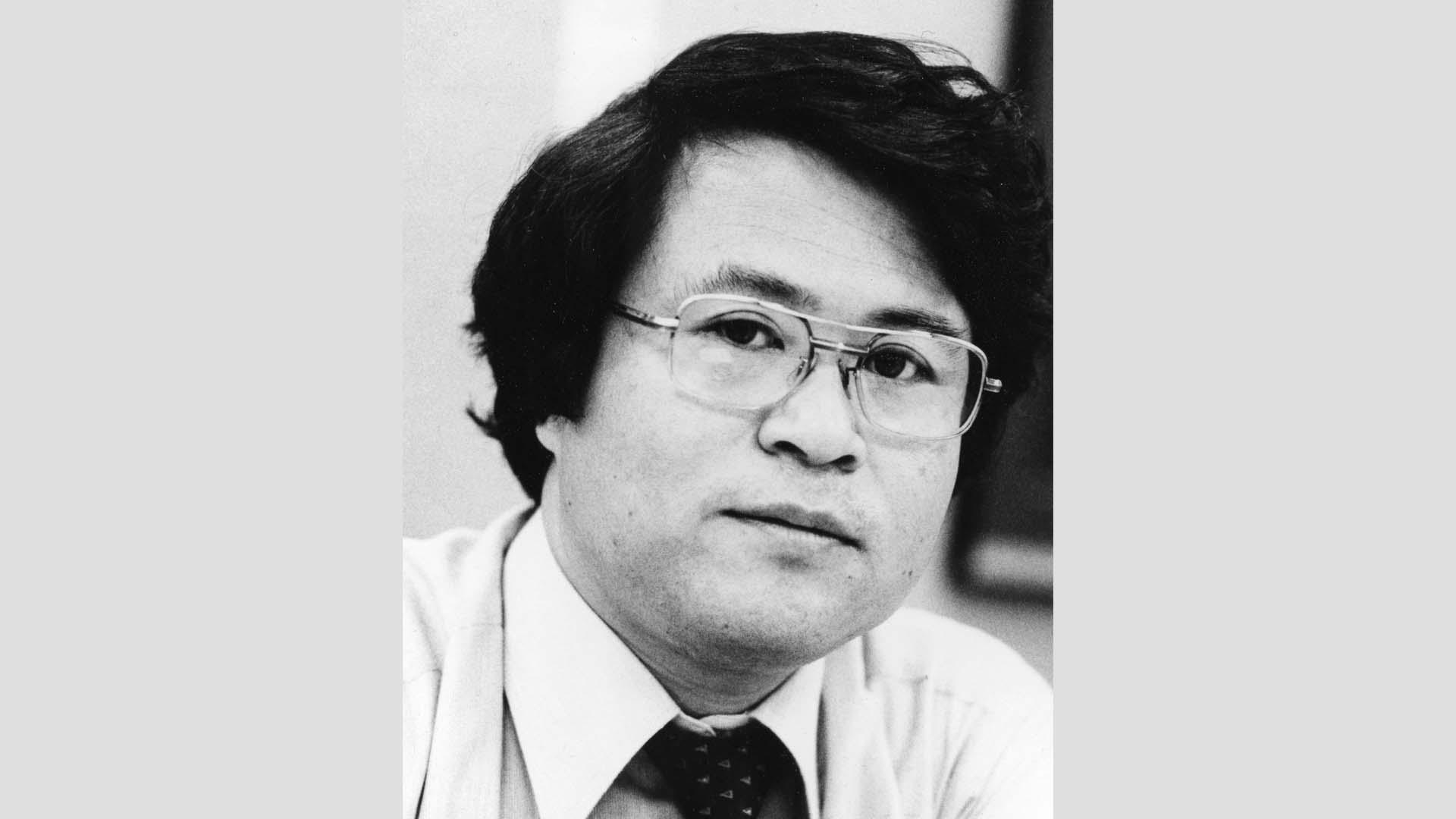

The 4004 emerged from a partnership between Intel and Japanese calculator company Busicom. In 1969, Busicom contracted Intel to design a microprocessor for a new desktop calculator. Prior to this arrangement, Intel had mostly dealt in the memory business. The project was tasked to Ted Hoff and Stanley Mazor, who were later joined by Federico Faggin and Masatoshi Shima. Faggin had the critical semiconductor expertise Intel was looking for, and Shima, a Busicom engineer, contributed his own experience to expedite the project.

The result of their collaboration, the 4004 processor, was released two years later and addressed a number of challenges in processor design. Before the 4004, processors had their logic programming hard-wired into the physical architecture, which usually consisted of many smaller components connected to multiple printed circuit boards (PCBs). They were not only complex to develop but had a large footprint. Moreover, each system was highly specialized and only served a single purpose.

Intel deemed this development method untenable and sought to design a chip that was more flexible, easier to integrate, and could serve a wider range of purposes. The company designed the 4004 with this key philosophy in mind. As a result, the chip condensed many of the previously discrete circuits into a single tiny package, reducing cost and product development time, and making it usable for a wider range of applications. The concept was revolutionary, and Intel hailed the chip as a “new era in integrated electronics.”

Although primitive by today’s standards, the 4004 had ground-breaking performance for its time. Built with 2,300 transistors, it featured a clock rate of 740 kHz and processed more than 90,000 instructions per second. Intel also managed to cram the memory and data bus into its standard 16-pin package, greatly reducing complexity and opening the pathways to smaller devices with varying amounts of storage and memory. The microchip could address a whopping 640 bytes of random-access memory, as well as 4 KB of read-only memory.

The chip also made it easy for system manufacturers to integrate into their products. Along with the 4004, Intel also released the 4001 ROM chips, 4002 RAM chips, and the 4003 shift register, creating a four-chip set. The 4004 only needed a single 256-byte ROM chip to work; computer manufacturers could use the processor’s internal register to do double duty as RAM, which was very costly at the time.

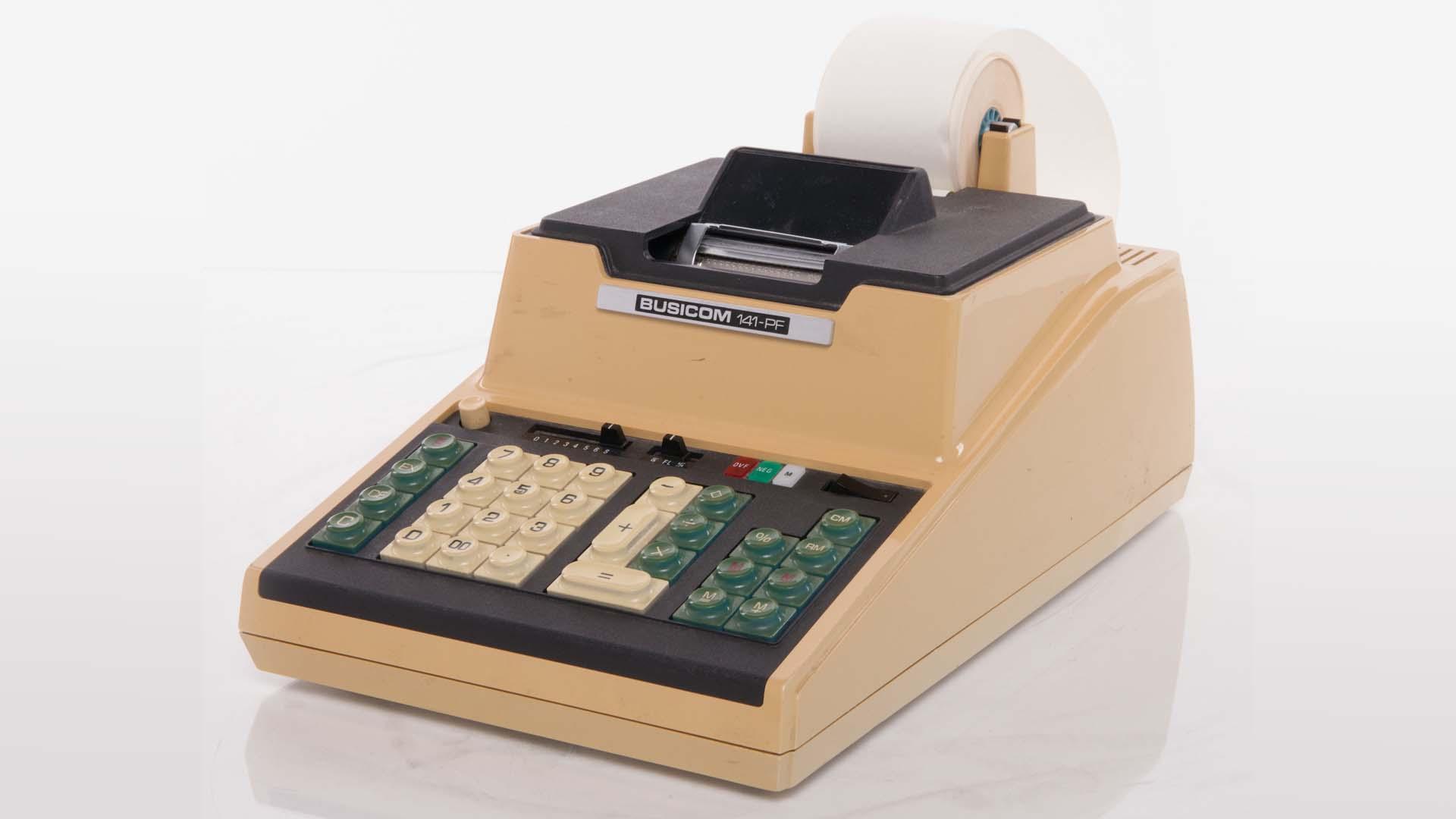

The first batch of chips went into the Busicom 141-PF calculator. Under its contract, Busicom had exclusive rights to the 4004 processor, but Intel convinced it to release the exclusivity in exchange for a discount on the chips. The chip saw some success after its commercial debut, making its way into several of Intel’s systems – computers, and a voting machine. But more importantly, it set the stage for the more powerful and ubiquitous Intel 8008 chip released just months after.

Busicom went out of business in 1974, but Intel had cemented a foothold in the microprocessors space. Today, the company is worth more than $200 billion. Its chips, as well as a plethora of other technologies, are found in all sectors of the technology industry. Although modern processors–built upon tens of billions of transistors and are infinitely faster–no longer bear any resemblance to the 4004, they all owe their roots to its stroke of ingenuity.