When more than 200 business leaders and IT specialists were asked if they knew the password policies of the various systems running in their building, or in some cases, parts of the building itself, the silence at the recent Data Connectors event in Toronto was deafening. Two people raised their hand, says the man who posed the question – Tony Anscombe, global security evangelist at ESET. Even those two didn’t seem very confident.

“There’s definitely a knowledge gap here…and this is only going to get worse,” he tells ITWC. It’s a gloomy statement but warranted. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT) have rapidly gained the attention of both enterprises and factories. Each industry has deployed swarms of chattering devices that generate, gather, and share data with other connected devices. It has lead to enormous efficiencies, as well as shiny new attack surfaces for hackers to exploit. Security is easily the number one issue when it comes to the adoption of IoT, according to Lou Lutostanski, Avnet Inc.’s global vice-president of IoT.

“People are afraid to tie things on to their network and their infrastructure,” he says.

But at least one global study from Trend Micro Inc. suggests they might not be afraid enough. Forty-three per cent of IT security decision-makers view security as an afterthought when implementing IoT projects, and only 53 per cent think connected devices are a threat to their own organizations. But meanwhile, nearly two-thirds acknowledge that IoT-related cybersecurity threats have increased over the past 12 months. The manufacturing industry, in particular, is shooting itself in the foot. A recent Vectra report says that compared to other sectors, the monthly volume of attacker detections per 10,000 host devices in manufacturing shows far more malicious internal behaviours.

Considering that the global manufacturing industry alone is projected to spend nearly $200 billion on IoT this year, after spending $190 billion the year prior, its inability to secure itself from within is alarming. Users in this space don’t know who has access to the data they generate – or if they’ve even created data – what that means for security, privacy, and also physical safety.

“IoT brings to bear the threat itself manifesting physically. In the past, we used to think of cyber threats as you getting hacked, losing data, it’s bad, and you might suffer financially, but life goes on. Generally speaking, your livelihood isn’t threatened,” explains Robert Arandjelovic, director of product marketing of the Americas at Symantec, which has a slew of IoT security solutions tailored to manufacturing and healthcare. “Medical equipment, cars, and other industrial spaces like power stations – they create a physical dimension to an attack.”

Quick Facts:

- Researchandmarkets.com says the ICS security market is expected to reach $24.93 billion by 2026, up from $12.02 billion in 2017, representing a compound annual revenue growth of 8.4 per cent.

- Revenue growth for partners selling data loss prevention and endpoint protection software in Canada grew more than 25 per cent in 2018, according to NPD Group. That’s the highest revenue growth among all security software segments.

A Cyber X report says nearly 85 per cent of industrial sites have at least one remotely accessible device, and 40 per cent of them have at least one direct connection the public internet. ICS systems are often controlled by obsolete Windows PCs, making them vulnerable to most malware. More than half of the surveyed industrial sites were running outdated versions of Windows.

For years the industrial sector turned a blind eye to the advancements in cloud and IoT largely due to the fact that they were disconnected from the world, says Barak Perelman, CEO of industrial cybersecurity firm Indegy.

“They were disconnected from the internet, disconnected from email servers and enterprise networks,” he says. “What happened though, technology caught up, and these manufactures suddenly understood it was impossible to separate their facilities from the outside world, and the main reason why was efficiency.”

In the process, however, they failed to overlap their OT and IT teams. They installed endpoint devices that didn’t conform to consistent standards, such as communication protocols and methods for configuration, making engineering, security, and management across these endpoints and the overall system next to impossible. It’s why attackers have been able to penetrate the factory floor, for example, and slowly worm their way into essential systems on the network.

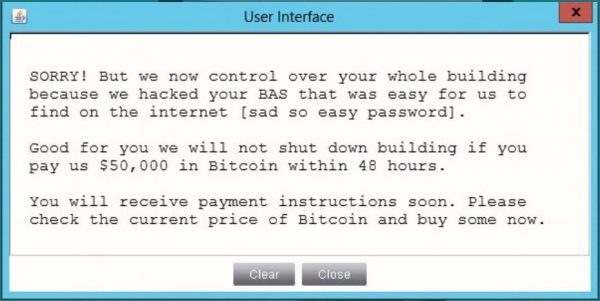

This powerful method, according to Anscombe, is how some attackers override temperature controls in a server room, allowing them to hold a company at ransom. Entire cities are potential targets as well.

In April 2018, a targeted ransomware virus called SamSam breached Atlanta’s network servers without warning, leaving city officials without access to critical records. A year prior, Russian hackers tricked staffers into entering passwords and used the most basic phishing tools to penetrate hundreds of U.S. utilities, manufacturing plants and other facilities. The December 2015 cyberattacks on Ukrainian power facilities inflicted actual damage to infrastructure and left 230,000 people without power during winter. At this point, one might wonder what chance a connected smart city has.

To be fair, it wasn’t until only a few years ago that manufacturing vendors like General Electric and Rockwell began introducing built-in security to their products, indicates Perelman. But that hasn’t helped IT, and OT teams better understand the importance of evaluating products, services, and vendors for essential security functions and services that ensure security responsibility is well assumed. It doesn’t help that as of today, there is no internationally recognized standard that can help companies reduce risks to their IoT solutions.

Is anyone doing something about this?

Technology vendors and their channel partners are doing their best to fill this gap.

Lenovo recently announced its quadrupling investments in IoT solutions and the channel in 2019, and that these investments can be seen in both its Data Center and Intelligent Devices groups. The technology vendor says it’s adamant about delivering complete end-to-end IoT solutions, negating the need for customers to rely on multiple vendors with different security solutions, a common pain point for many IoT adopters. Prepackaged Lenovo IoT solutions that include hardware, software and services for the channel can be expected later this year.

In February, Indegy announced a channel partnership with government IT solutions provider Carahsoft Technology Corp., giving the public sector access to the Indegy Industrial Cyber Security Suite. The suite of products is delivered as an all-in-one turnkey appliance that plugs into the network without the use of agents. It’s available in Canada, and accessible through its partner network, which includes Kitchener-based Brock Solutions.

Naturally, BlackBerry has zeroed in on IoT security, too. The company announced plans in January to apply its trusted security software, currently found in smartphones and vehicles, to a broader range of IoT devices in 2019.

Avnet has also stepped up. Earlier this year, the distributor teamed up with Octonion, an intelligent edge IoT software provider, as well as Microsoft Corp., to launch an online portal called Brainium that’s linked to Avnet’s new IoT SmartEdge Agile sensors. The Brainium platform is equipped with embedded security features and machine learning functions for predictive maintenance.

It’s made to help engineers and manufacturers deploy IoT projects from the design stage with pre-installed AI and security at the edge of the network. Instead of sending it across long routes to data centres or clouds, edge computing allows data produced on IoT devices to be processed closer to where it’s created, yielding all sorts of benefits. It’s where the true value of IoT ultimately shines.

The project has been in development for more than a year, says Lutostanski.

“Software is becoming a bigger part of solutions and products in the IoT space. Allowing people who aren’t data scientists to use AI on the edge, and to do so in a very cost-effective method on very low-resource devices is a big step forward.”

Octonion CEO Cedric Mangaud says it would be nice if other manufacturers and distributors replicated Avnet’s strategy.

“I’ve never seen a distributor tackling the software play so aggressively,” he told ITWC during Octonion’s launch at CES in January, where he confirmed at least one Canadian corporation has shown significant interest in the solution. “They have the vision and developed a strategy to change the way IoT is sold. I think they also realized that selling hardware is not where the value lies.”

Arandjelovic applauded the unlikely duo’s efforts.

“They’ve done a good job of addressing a market need,” he says, pointing out how he’s refused to connect recently purchased motion-sensing night lights to the internet. “The likelihood that the company that made them hired a security expert for $200,000 a year to ensure their $12 motion-sensor light is not a security weak spot is minimal.”

IoT is a force multiplayer for cyber risk, and Anscombe encourages both small businesses and large industrial companies to follow a few basic steps to greatly minimize that risk. First, ensure IT and OT teams understand the risks imposed by new or existing IoT devices that are connected to the internet and the corporate network. Challenge IoT providers to demonstrate the effectiveness and maturity of the security in their solutions, lean on channel partners, and please, he says, “Make sure you’re not just going to the Source to buy your sensors and webcams.”